“Can someone who has no art background follow along with the exhibit easily, especially given the large amount of information presented?” This is the question guest curator Shelly Bahl and lead archivist Anita Sharma asked themselves as they embarked on the exceedingly fast-paced six-month long journey to document Chicago’s South Asian American art history scene across the decades. Hosted by the South Asia Institute (SAI), the ambitious exhibition What is Seen and Unseen: Mapping South Asian American Art in Chicago navigates the intricate histories and contributions of South Asian American art in Chicago as “the first comprehensive exhibition to map and disseminate this vital chapter of Chicago’s art history” (SAI). The multifaceted exhibition, comprising two parallel shows – Shadows Dance Within the Archives, an archival exhibition of over 125 years of under-documented exhibition and cultural history, and Are Shadow Bodies Electric?, a thematic exhibition featuring eight contemporary artists who are creating surreal and/or unclassified shadow bodies that exist outside of time, place and space – delves into the processes, challenges, and narratives that define the South Asian American art scene. It presents a blend of historical, cultural, and artistic perspectives chronicled from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition to the contemporary era of 2020s Chicago-based artists.

Guest-curated by New York-based interdisciplinary artist and curator, Shelly Bahl, with the support of arts archivist, Anita Sharma, What is Seen and Unseen carries the dual burden of being both an art exhibition and the telling of an historical and cultural narrative. Centering the idea of community archiving, the team was deeply committed to community engagement from the outset. With an initial scope of exploring a history of 25-30 years, as the project was conceptualized, it became evident to Bahl and Sharma that a broader historical context was necessary.

The project kicked off with a town hall in Fall 2023, where artists and community members were asked to bring archival material, such as ephemera and printed materials, which they felt would best represent their living legacy. This material was collected as part of the community-led project to guide the exhibition and highlight the discursive nature of the South Asian American art ecosystem in Chicago. The project included a mix of both physical and digital materials and artwork, collected from personal archives, homes, and hard drives, as well as from institutional archives.

This participatory approach not only enriched the exhibition but also highlighted the significance of community involvement in creating an historical record. This community-led approach was instrumental in uncovering lesser-known histories and contributions, ensuring a more comprehensive representation of the South Asian American art scene in Chicago.

Community meeting on November 18, 2023 to begin community consultations and studio visits, South Asia Institute. Photo courtesy of Shelly Bahl.

One such instance was the significant re-discovery of the artist and photojournalist Mukul Roy, whose contributions might have been overlooked without the diligent research conducted by the lead archivist. Upon scouring exhibition lists on institution websites and timelines one by one for names from the diaspora, Sharma came across Roy’s name in passing among the Chicago Cultural Center’s exhibition listings. Bahl and Sharma reached out to community members to inquire about any knowledge regarding this figure. It turned out that Roy had a number of connections and contemporaries who were impacted by her work and who functioned in the same spaces she had back in the 80s and 90s. The project also unearthed the little known Chicago histories of figures like renowned art historian, Dr. Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, who had his first solo show in Chicago in 1920. The research also resulted in the recognition of the contributions of artists and community organizers such as Sadia Uqaili and Zafar Malik, who have significantly impacted their neighborhoods and communities. The spotlight on Roy and other overlooked artists underscores the importance of the team’s thorough and continuous research, even under significant constraints, such as limited access to archives, lack of public histories, and the exploration of an immeasurable amount of material in a limited time frame.

Additionally, it was important for curator Shelly Bahl to orient the project with a multidisciplinary lens, focusing not just on visual art but on other perspectives and forms as well, which is why there is such a distinct inclusion of film/video, performance arts, curators, and community organizers, and the cultural ethos of certain historical periods. The arrangement of the materials in the exhibition illustrates how the curator was trying to frame the project. Chronologically starting from the 1893 World’s Fair, the exhibit moves on to depict what the South Asian diaspora was doing in Chicago, how it existed, and how it expressed itself – through forms other than just visual arts to begin with – to illustrate how the diaspora has manifested its identity and culture through diverse artistic expressions over time.

A central concern for the team was accessibility, particularly for visitors without a background in art. Given the extensive information presented, the exhibition utilizes a combination of display cabinets, written texts, and QR codes. To manage the wealth of information without overwhelming visitors, many labels are accessed via QR codes, which are also available as a nine-page document for those preferring not to use their phones. This approach allows for a streamlined visual experience, avoiding excessive text on the walls and ensuring the archival material remains the focus.

Studio visit with artist Janhavi Khemka. The artist is hearing impaired and so the conversation was conducted in-person via an audio to text app. The artist’s disability greatly influences the conceptual and experiential nature of her artwork. Photo courtesy of Shelly Bahl.

Highlighting the discursive nature of the project, Bahl’s curatorial intentions actively aim to emphasize that the history presented is not monolithic but a rich tapestry that evolved over time. According to the team, the title says it all – both Bahl and Sharma knew there was a complex history of their community in this city, they just didn’t know all the sites in which it was located.

Following the initial kickoff event for the project (the town hall that took place in fall of 2023) where artists and community members were asked to come with archival material and ephemera, Bahl, and Sharma turned their efforts towards digging through available archives to uncover further context and histories, oftentimes making discoveries from the contemporary era. When we think about archives, we tend to think about people who are not here or what is described as “dead” texts and materials, but for this project the curatorial team was working closely with numerous contemporary artists and items from their collections. The team described the process through an archaeological lens, where one goes on a dig and finds certain artifacts, ideas, and people; researches them, both textually and communally; and returns to the site or subject for further exploration thereafter. Bahl reflected, “it’s really a layering process… You might find something, and then you do more research, and you find something else that you didn’t expect. It’s like an archaeological dig, and we kept finding new layers as we went along.” The employment of such methods really empowered the community to become interested in the work and engage in digs themselves.

The involvement of the community is what really defined the significance of the exhibition for Bahl and Sharma, who expressed that the strength of a community archiving project is that it pushes people to come together to do a certain kind of history-telling and meaning-making work through participation and a genuine understanding of its value. The project not only empowered the community to become interested in archiving but also highlighted the strength of a community-driven approach. Continuous involvement of the community allows these histories to remain at the forefront, highlighting the significance of the community’s role in history-making and history-telling.

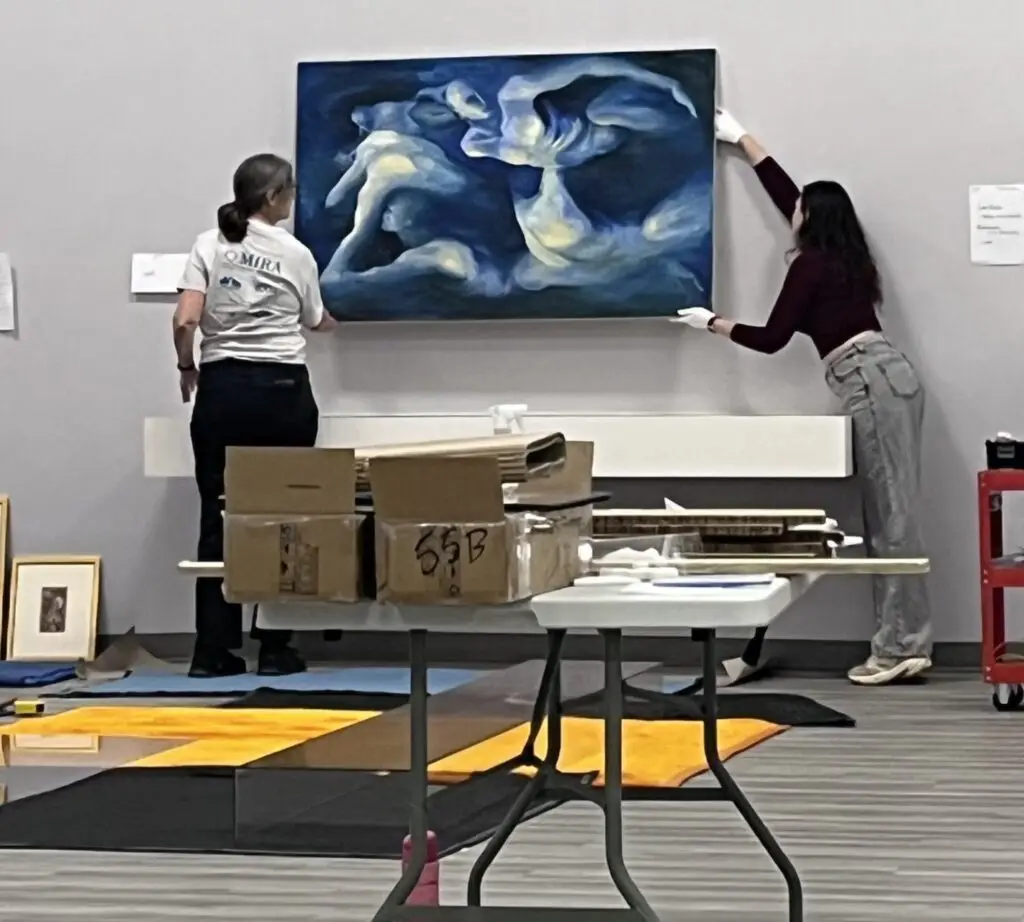

Gallery installation-in-progress with the work of Lala Rukh, What is Seen and Unseen, South Asia Institute. Photo courtesy of Shelly Bahl.

Future Prospects

The materials gathered during the project have been digitized and stored on a dedicated hard drive at SAI, ensuring their accessibility and continued use. The compilation of a digital archive is in the works and the hope is that it will be cataloged and shared according to current standards, making it interoperable and accessible not only to other institutions but to individuals as well. “One of the key things we wanted to do was to give back to the artists, especially with digitization,” Sharma emphasized, highlighting the project’s commitment to preserving and sharing the artists’ contributions. She further noted that “the digital archive will be an invaluable resource, not just for researchers but for the artists themselves, who often lack access to professional archiving of their work.” The curators hope that the groundwork laid by this project will inspire future initiatives and encourage deeper dives into specific aspects of the South Asian American art scene in Chicago.

However, the six to seven-month timeframe imposed significant pressures on the team. Bahl reflected on the accelerated pace, noting, “This is a two to three-year project, but the fast pace came at a cost.” The team had to engage in intense, often serendipitous research, scouring archives, institutional websites, and exhibition lists to uncover historical details. Despite these constraints, Bahl and her team were committed to producing an exhibition that was both comprehensive and representative of the South Asian American art scene in Chicago. As Sharma poignantly concluded, “In the end, it was a labor of love, and while we faced numerous challenges, the dedication and passion were what drove us forward.”

The project has laid a strong foundation for further exploration and collaboration, empowering the community to take an active role in preserving and celebrating their cultural heritage. The exhibition has opened up new avenues for research and highlighted the importance of community involvement in creating historical records. Bahl and Sharma’s dedication and vision for this community-driven archive project are crucial, emphasizing that the work must come from within the community to be truly meaningful. Serving as a call to action for more comprehensive and inclusive archiving efforts, the work of the curatorial team and South Asia Institute are leading steps towards ensuring that the diverse histories and contributions of South Asian American artists are recognized and preserved as part of the city’s historical and cultural narrative.

What is Seen and Unseen: Mapping South Asian American Art in Chicago is on view through October 26, 2024 at South Asia Institute.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Fariha M. Koshul

Fariha Koshul, a Chicago-based writer for Terra Foundation for American Art, combines her academic training in ethics, anthropology and sociology with practical experience in digital curation, collections management and archiving. Her time at the University of Chicago involved leading research projects and collections care aimed at incorporating ethical practices in diverse cultural contexts. Fariha’s work is marked by a deep commitment to an understanding of the ethical implications of working with anthropological material, specifically in curatorial and museum spaces, and to the promotion and preservation of cultural, artistic and faith-based narratives and communal and social histories.