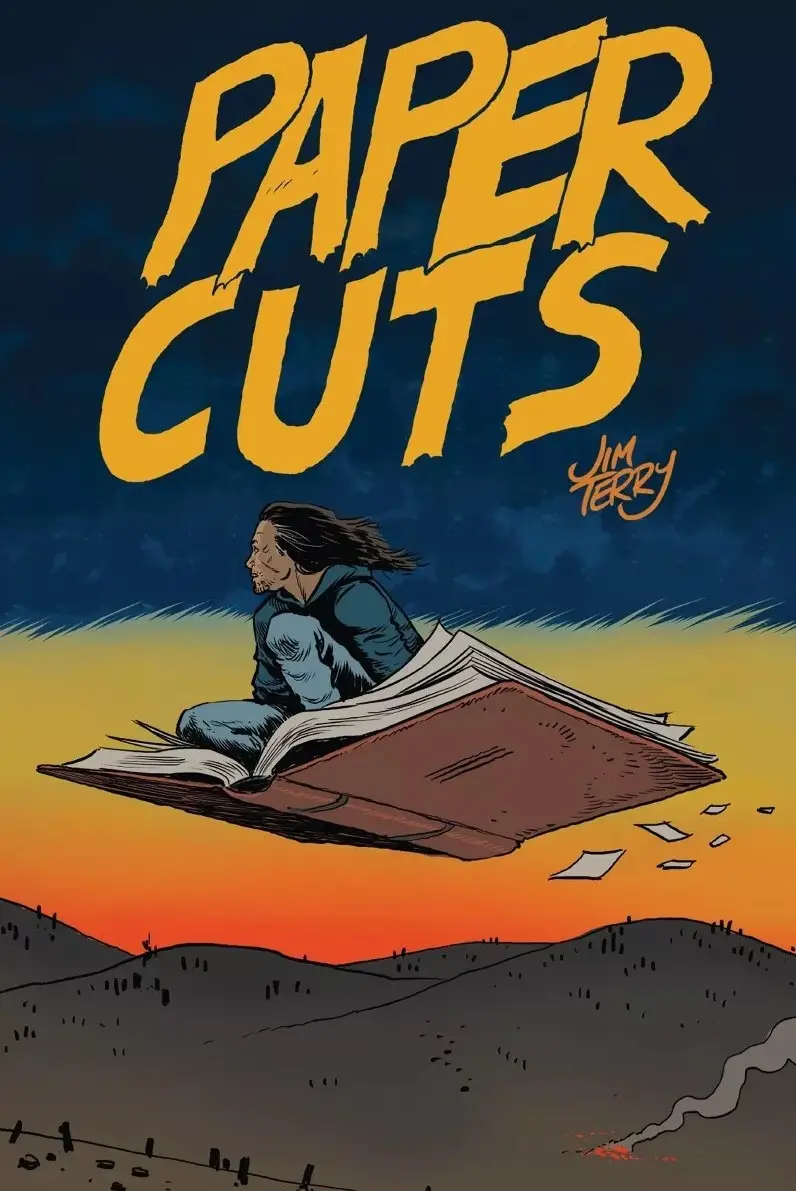

In a world shaped by colonial legacies, the act of creating art is often an act of defiance. For Ho-Chunk visual artist Jim Terry, author of the comic Paper Cuts, defiance is more than a creative impulse–it’s a way of life. His work, featured in the Newberry Library’s Indigenous Chicago exhibition, challenges conventional boundaries of historical narratives and heritage preservation. Through his unique blend of adversarial spirit and joy as resistance, Terry reclaims storytelling as a tool to confront historical erasure, personal trauma, and systemic oppression.

The Newberry Library’s Indigenous Chicago exhibition explores the city’s rich Native history, highlighting the enduring presence and contributions of Indigenous communities from the seventeenth century to the present (Chicago Archivists). This multifaceted initiative, a collaboration between the Newberry Library, the Chicago American Indian community, and tribal nations who have ancestral ties to Chicago, features digital resources, interactive maps, and public programs that reposition Chicago as Indigenous land and space (Indigenous Chicago). By platforming Indigenous voices, the exhibition challenges historical erasure and emphasizes the dynamic aspects of Native life in Chicago.

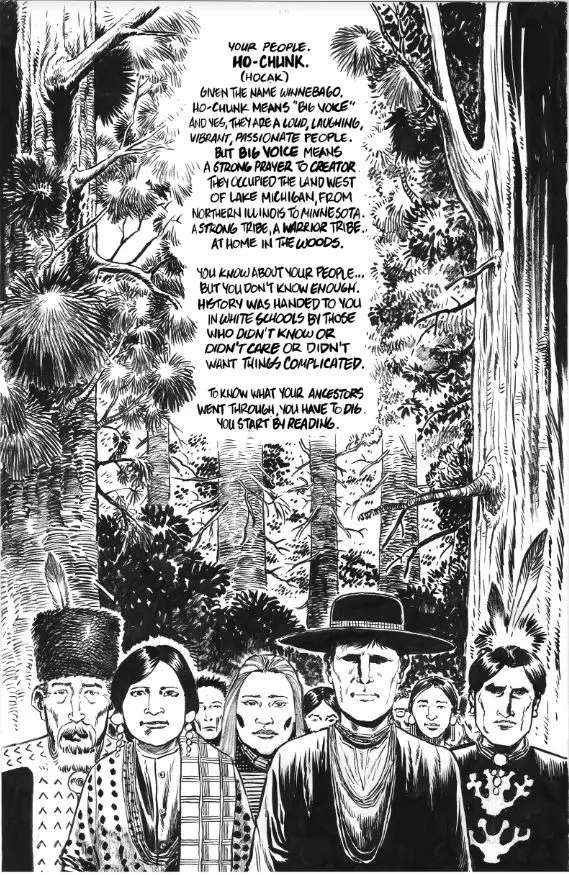

Terry’s Paper Cuts was developed during his time in an artist residence at the Newberry Library, where he was invited by curator Analú María López to engage with the library’s extensive collections. This process involved delving into materials that connected him to both his Ho-Chunk heritage and Chicago’s Indigenous history. Reflecting on the experience, Terry described feeling both overwhelmed and inspired by the immense archival resources. Initially considering a broader historical depiction, he ultimately chose to focus on his personal narrative, crafting a story that blends his own experiences with the collective memory of displacement and resilience. The comic opens with a nod to his time at the Newberry, setting the stage for a work that balances intimate reflection with historical critique.

Paper Cuts weaves together Terry’s personal journey of grappling with his Native heritage and the intergenerational trauma that shaped his identity. Raised in a predominantly white suburb and distanced from his cultural roots, Terry recounts his family’s history of forced assimilation through residential schools and his own struggles with invisibility and internalized disconnection. The story explores themes of cultural erasure, resilience, and self-reclamation, culminating in a message of hope and a plea to embrace joy as an act of defiance. Paper Cuts blends raw honesty with visual storytelling, offering a deeply personal perspective on the complexities of identity and history.

The Adversarial Spirit as Fuel

Jim Terry describes himself as “an adversarial-based person.” For him, the adversarial spirit is not about mindless rebellion but a deeply rooted response to exclusion and elitism.

For Terry, being part of an exhibit at a prestigious institution like the Newberry Library was both unexpected and transformative. Paper Cuts, commissioned specifically for the exhibit, resists the traditional confines of “fine art.” Instead, it offers a deeply personal narrative that bridges the gap between academic presentation and visceral emotional engagement. “I intentionally did [the comic] in arrogant defiance of anything that the fine art world might find palatable,” Terry says in an interview. “I just wanted to do something that anybody could understand.”

That defiance was necessary for Terry, whose early encounters with the art world left him feeling alienated. “The Native fine art scene is different from anything that I’ve experienced, as is any fine art scene to working artists. And it’s absolutely elitist. And that’s one of the things that surprised me about being asked to participate in this because comic books in general have always been considered the sort of gutter medium. And I don’t see it that way. I never have.” Yet, in Paper Cuts, Terry’s comic medium becomes a leveling force, inviting viewers to step into his story, his pain, and ultimately his hope. With Paper Cuts, he creates a piece that unapologetically asserts the value of comics as an art form while rejecting the conventions of the fine art world. The result is a deeply personal narrative that reflects Terry’s own struggles with identity, belonging, and resilience in the face of collective trauma, violence and erasure. His story is one of rediscovery and reclamation, a process that culminates in his role as an artist speaking to his personal experiences of being Native.

Terry’s resistance to categorization extends beyond his medium. As a Native artist raised in a predominantly white suburb, he has often felt disconnected from both mainstream art spaces and Native cultural practices. Yet this “otherness” has become a source of creative power. “I realized that rather than try to represent the entirety of the Native experience or the Chicago urban experience, I should just tell my story,” he says.

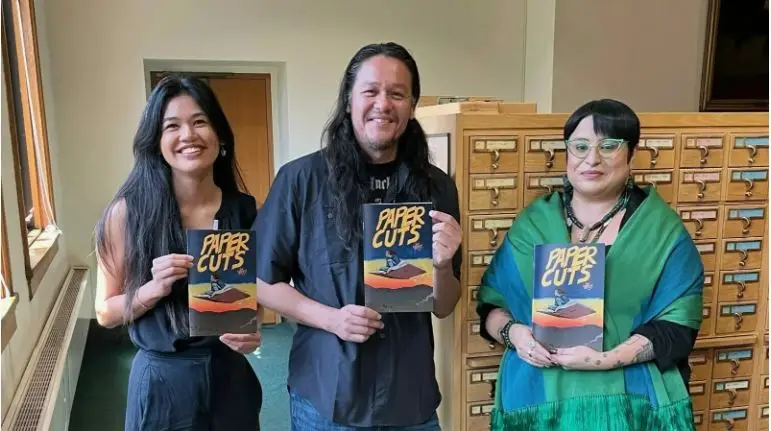

The Newberry’s Haku Blaisdell, left, and Analú Maria Lopez greeted Jim Terry when he delivered copies of Paper Cuts prior to the opening of Indigenous Chicago. Photo courtesy of the Newberry Library.

Joy as Resistance

At the heart of Terry’s work lies a philosophy of joy as resistance. In Paper Cuts, this philosophy manifests in his refusal to let trauma define his narrative. While the comic explores heavy themes—generational trauma, cultural disconnection, and systemic oppression—it ends with a plea to embrace joy. “Any minute that my joy is taken from me is a minute that they win,” Terry says. “I want to defiantly enjoy my life in spite of whatever is going on.”

This commitment to joy is not about ignoring pain but about transcending it. For Terry, joy is a form of resilience that allows him to reclaim his identity and his place in the world. “We’re still an occupied people, and we’re still finding our way,” he acknowledges. “But resilience, though overused, holds real meaning. It gives me strength.”

Terry’s focus on joy also informs his plans for future projects. “I’d love to tell stories of kindness and humor,” he says. “Natives are really funny, and it’s important to breathe a little after reading something heavy.”

Colonial Histories and Contemporary Resistance: Storytelling as a Tool for Change

Terry’s adversarial approach and joyful defiance resonate deeply in a world still grappling with the legacies of colonialism. Paper Cuts places Terry’s personal narrative within the broader context of U.S. history, where the genocide of Native peoples has been obscured by triumphalist myths. The comic offers a counter-narrative, one that centers the history of violence, collective suffering and resilience.

This framework aligns Terry’s work with contemporary movements like the Palestinian solidarity protests in Chicago. “There’s a shared experience of displacement, erasure, and resilience between Native peoples and other marginalized communities,” Terry notes. His work, like the art emerging from these movements, becomes a form of resistance that humanizes and reclaims histories often told from the perspective of the oppressor.

At its core, Paper Cuts is an act of storytelling, a medium Terry believes is essential for creating empathy and change. “The only way I can operate is by speaking strictly of my own experience,” he says. “I can’t speak for anyone else, but I hope that my story resonates and makes people look at things differently.”

This emphasis on personal truth allows Terry to address universal themes without attempting to represent all Native experiences. His work speaks to the power of individual narratives to illuminate broader struggles, bridging the personal and the political.

A page from Jim Terry’s Paper Cuts.

From Standing Rock to the Art World

Terry’s philosophy has been shaped by experiences like his time at Standing Rock, where he witnessed a radically different approach to resistance. “The wisdom I heard there was so antithetical to how I was raised,” he recalls. “When the Dakota Access Pipeline guys sent insurgents into the camp, the response wasn’t violence. It was to invite them to dinner and tell them, ‘We’re doing this for your children too.’ That blew my mind.”

This philosophy of inclusion and empathy informs how Terry engages with institutions like the Newberry Library. While he remains critical of the art world’s elitism, he appreciates the freedom the Newberry gave him with the commission. Terry’s approach to Paper Cuts was shaped by the creative freedom granted by the Newberry Library. “They gave me complete freedom,” he recalls. “If they didn’t like what I produced, I would’ve published it myself. That small bit of freedom gave me the leeway to create something deeply personal.”

The Newberry Library’s inclusion of Paper Cuts represents a step forward in how historical exhibitions can engage audiences. Terry notes, “The exhibit was dry to me in some places—academic, even. But they did something profound by letting my work exist there without censorship. They allowed it to breathe, and in doing so, it gave life to the entire show.”

This approach offers a roadmap for other institutions aiming to make history more accessible and engaging. By integrating contemporary, emotionally resonant artists like Terry and works like Paper Cuts, they can transcend the limitations of traditional academic displays and connect with audiences on a human level.

As Paper Cuts continues to resonate with viewers, it reaffirms the power of personal storytelling in historical contexts. For Terry, the comic is more than an artistic endeavor; it is a way to share his truth and, in doing so, transform how others see the world.

A Transformative Role in Historical Exhibitions

For many visitors, Paper Cuts serves as the emotional center of the Indigenous Chicago exhibit. While the exhibit features a wealth of historical artifacts, Terry’s comic provides a humanizing counterpoint. One visitor remarked, “When I was flipping through the comic, it shifted my entire perspective of the exhibit. Every map I looked at or plaque I read after was reframed through the emotional context Paper Cuts brings.”

Terry himself was moved by seeing his work included in the exhibit. “To walk through that exhibit and see my book as part of this massive collection of Indigenous history was humbling and terrifying,” he says. “I didn’t feel like it belonged there, but seeing it placed alongside these monumental artifacts made me understand how it could provide a different kind of representation.”

This emotional resonance is what sets Paper Cuts apart. By integrating a personal, visceral narrative into a traditionally textbook context, the comic bridges the gap between historical representation and emotional engagement. It allows viewers to see history not as a static collection of facts but as a living, breathing continuum of human experience. Through Paper Cuts, Terry bridges the gap between academic history and lived experience. For many visitors, the comic serves as the emotional heart of the Indigenous Chicago exhibit. One attendee described it as “an integral part of the exhibit, a piece that reframes every other element through its emotional context.”

This impact underscores the importance of integrating personal, visceral narratives into historical exhibitions. By doing so, institutions can make history more accessible and engaging, fostering connections between the past and the present.

The Legacy of Defiance and Joy: Empathy, Connection and Beyond

For Jim Terry, art is not just a medium but a philosophy. His work embodies the adversarial spirit and joyful defiance that have sustained marginalized communities for generations. In Paper Cuts, these values come together to create a piece that challenges, inspires, and transforms.

As Terry continues to create, his work serves as a testament to the power of storytelling, the necessity of resistance, and the resilience of joy. In a world still grappling with the legacies of colonialism and systemic oppression, his voice offers a reminder that art can be both a weapon and a refuge—a way to confront the past while imagining a better future. For Terry, the ultimate goal of his work is to inspire connection. “At our core, we’re all human beings,” he says. “If I can get someone to empathize with my story, maybe it makes them look at something differently.”

Through Paper Cuts, Terry achieves this goal. His comic not only reclaims his narrative but also transforms how others see the world. It is a testament to the power of art to transcend boundaries, challenge conventions, and create lasting change.

As Paper Cuts continues to resonate with audiences, it affirms the importance of centering personal, emotionally engaging narratives in historical contexts. For Terry, the comic is not just an artistic endeavor—it is a declaration of life, a celebration of joy, and a powerful act of resistance.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Fariha Koshul

Fariha Koshul, a Chicago-based writer for Terra Foundation for American Art, combines her academic training in ethics, anthropology and sociology with practical experience in digital curation, collections management and archiving. Her time at the University of Chicago involved leading research projects and collections care aimed at incorporating ethical practices in diverse cultural contexts. Fariha’s work is marked by a deep commitment to an understanding of the ethical implications of working with anthropological material, specifically in curatorial and museum spaces, and to the promotion and preservation of cultural, artistic and faith-based narratives and communal and social histories.