The upcoming exhibition Woven Being: Art for Zhegagoynak/Chicagoland, opening in January at the Block Museum of Art, asks the question, “What would it mean if Indigenous people with ties to this land were the point of entry to Chicago’s art history?”

Woven Being is one of six Native-centered exhibitions taking place this fall and winter as part of Art Design Chicago. Guided by Indigenous voices and practices, together this series of exhibitions showcases the breadth and depth of artwork by a diverse group of Native artists with ties to the region, while embracing Indigenous ways of knowing and seeing the world. Indigenous artists don’t simply show their work in these exhibitions; they have the decision-making authority for how their stories are told. The series includes:

Gagizhibaajiwan, Center for Native Futures, June 15 – December 14, 2024

Chicago Works | Andrea Carlson: Shimmer on Horizons, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, August 3, 2024 – February 2, 2025

Indigenous Chicago, Newberry Library, September 12, 2024 – January 4, 2025

Still Here: Linking Histories of Displacement, National Public Housing Museum, Opening January 2025

Woven Being: Art for Zhegagoynak/Chicagoland, The Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, January 26 – July 13, 2025

Living Stories: Contemporary Woodland Native American Art, Mitchell Museum of the American Indian, January 27, 2025 – January 5, 2026

Long before European settlers came to the Chicago region, it was home to the Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, Miami, and other Native American tribes and nations. Chicago is one of the major population centers for Native Americans in the country and home to the largest Native population in the Midwest. Despite their constant presence, I was unable to find evidence of the last time Native artists were the primary focus in more than a handful of exhibitions happening concurrently in notable art institutions in this city. In fact, the first iteration of Art Design Chicago, which reached its public phase in 2018, included no exhibitions centering Native artists. Indigenous artists from Chicago and those from nations forcibly displaced from the area in the nineteenth century are elevating their stories through contemporary art practices, merging loss and activism to reinforce legacy. They are being recognized today, but their work is not finished. It is work in progress.

“How do we reconcile what cannot be reconciled?” is the question raised by Gagizhibaajiwan, the exhibition at the Center for Native Futures curated Lois Taylor Biggs (Cherokee Nation/White Earth Ojibwe). The artists in Gagizhibaajiwan, including interdisciplinary artist Marcella Ernest (Gunflint Lake Ojibwe/Bad River Band of Lake Superior), sculptor Michael Belmore (Anishinaabe from Lac Seul First Nation), weaver Renee Dillard (Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians), and painter Zoey Wood-Salomon (Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory), interpret the story of Misshepezhieu, the Underwater Panther who lives below the water, and Animikii, the Thunderbird who lives in the sky, evoking Anishinaabe teachings on duality, ambiguity, and balance. I can’t help but compare the whirling of constant conflict and relation of Misshepezhieu and Animikii with Native communities and the forces that uphold borders and racist ideologies. The dual tension explored in this exhibition carries over to the other exhibitions.

Zoey Wood-Salomon, Journey Across the Great Lakes, 2024.

The idea of mending the harm inflicted on Indigenous peoples is a fantasy–we can’t go back and stop the massacres. The words of revolutionary activist Mariam Kaba echo in my reflection for this article: “Hope is a discipline.” This is a mantra I murmur constantly in the face of everyday injustice. As art institutions across the nation consider what it means to be equitable, it is important to ask how they include Native artists and curators. By witnessing the art in these exhibitions, I now realize the importance of the word “center.” Beyond creating community, at the Center for Native Futures the organizers remind us to center Natives.

The participating artists in these six Art Design Chicago exhibitions (as announced up to the time of writing this article) have been breaking barriers in art institutions for years. Native artists are working to provide safer spaces for Native peoples to be included in institutions of power. When the Indigenous curators and artists involved speak into the mic at openings and panels, and in conversations with each other, they share frequent reminders to give artists their flowers for creating and being involved with the contemporary Native North American art world. I admire the community doing the work, which I know is both exhausting and important.

Andrea Carlson (Ojibwe/European descent), co-founder of the Center for Native Futures, has been at the forefront of this movement in the Midwest. Carlson, based in Northern Minnesota and Chicago, considers how landscapes are shaped by history, relationships, and power. Her solo show, Andrea Carlson: Shimmer on Horizons at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA), reflects on how land carries memories of colonial expansion and violence, as well as Indigenous presence and resistance. I had the opportunity to witness the artist in conversation with MCA curatorial assistant Iris Colburn. I find it so brave that her painting, Perpetual Genre, depicts cannibals in the style of roman sculptures. I giggle as I take in Carlson’s humongous horizon paintings that layer tropes and myths surrounding Native histories. Later, during the conversation, Carlson shares, “There is so much anxiety about loss, but we have the power of memory work.” She brings up the memories that we carry in our bodies, in our hands. She takes a moment to remember the history of the land where the MCA stands, the devastation that the Council of Three Fires faced after the 1829 Lake Michigan Treaty fraud, and before that, and still today. The truth is that many people did not abandon this area—their removal was forced. It should feel good to come back.

Andrea Carlson, Perpetual Genre, 2024. Oil, acrylic, gouache, ink, color pencil, and graphite on paper; overall: 45.5 × 61 in. (115.6 × 154.9 cm). Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, Block Board of Advisors Endowment Fund purchase, 2024.2a-d. © Andrea Carlson. Courtesy of the artist and Bockley Gallery.

Opening in January, Still Here: Linking Histories of Displacement at the National Public Housing Museum will use art, archives, and public dialogue to explore and connect the histories of displacement of Indigenous people and African American families on the land where the museum is located. We have a right to know about the lands we occupy—what actually happened here and what continues to happen. As part of the exhibition, Andrea Carlson has created a temporary mural on the outside the museum entitled Still Here: Zhegagoynak, which depicts the shared histories of forced removal and displacement of Black and Indigenous people. It links the harm of redlining experienced by African Americans to the 1821 Treaty of Chicago, the 1816 Treaty of St Louis, and the 1795 Treaty of Greenville. Written in Potawatomi and English, the mural’s text, “Potawatomi Land,” serves as a gesture to the possibility of healing through truth-telling.

Left: Chris Pappan, Spirit of Kitihawa, 2020. Pencil, graphite, ledger paper, inkjet, (Private Collection). Right: Tonika Lewis Johnson, 6823 South Aberdeen, 2022. Photograph and Original Landmarker.

Andrea Carlson is also one of four Indigenous artists with connections to the Chicago area who are partnering with the Block Museum of Art on Woven Being: Art for Zhegagoynak/Chicagoland, which opens January 26, 2025. The collaborating artists, including Carlson, Kelly Church (Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Tribe of Pottawatomi/Ottawa), Nora Moore Lloyd (Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe), and Jason Wesaw (Pokagon Band of Potawatomi), are creating “constellations” of their own artwork alongside historical and contemporary artworks by other Indigenous artists of the region. Woven Being will present more than 80 works by 33 artists that speak to the diversity of Indigenous art, materials, and time. Embracing Indigenous curatorial methodologies that prioritize collaboration, reciprocity, and sustained dialogue, the Woven Being team seeks to advance knowledge of Indigenous art and its interconnectedness in this place we now call Chicago. According to the exhibition’s Guest Co-Curator Jordan Poorman Cocker (Kiowa), “Recognizing and coming to new understandings about how land-based or place-based histories can reinform how to tell stories about Indigenous art is critical.”

Nora Moore Lloyd (Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Ojibwe, born 1947), Birchbark/Wiigwaas,[recto] 2020. Photograph on fabric, two-sided, 50 x 84. Courtesy of the artist.

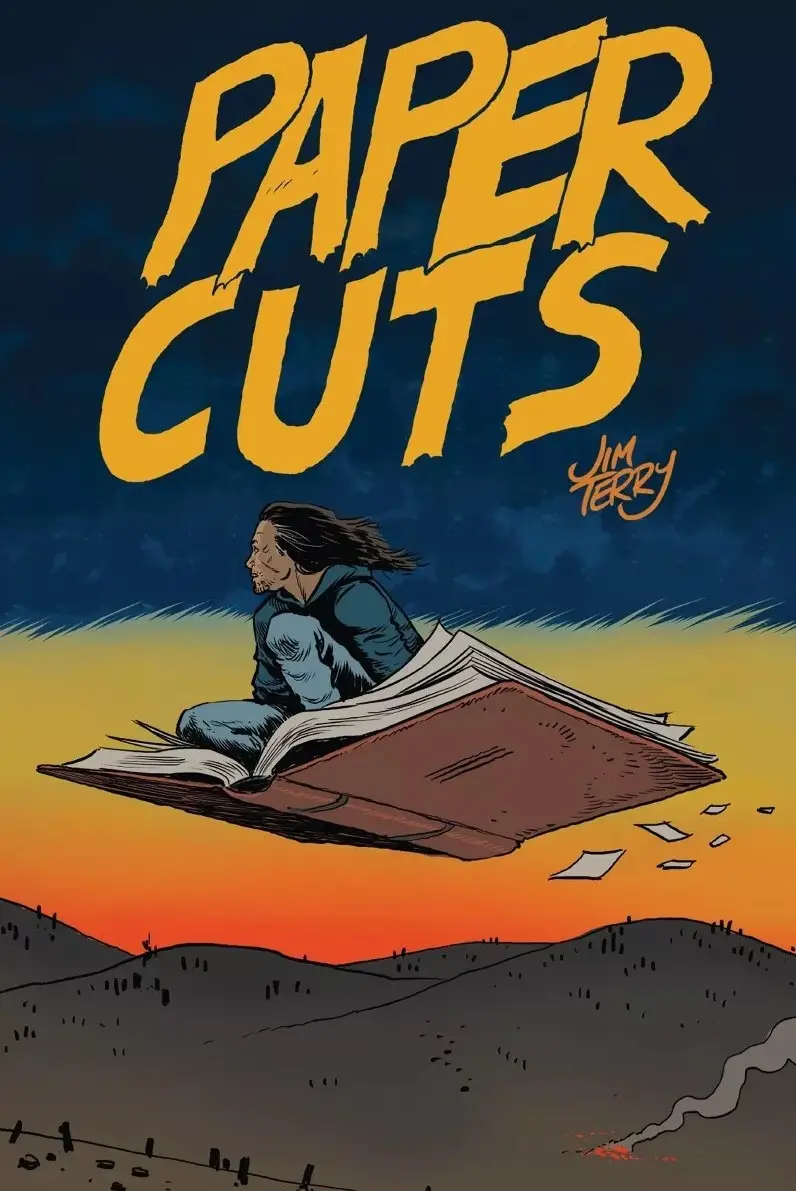

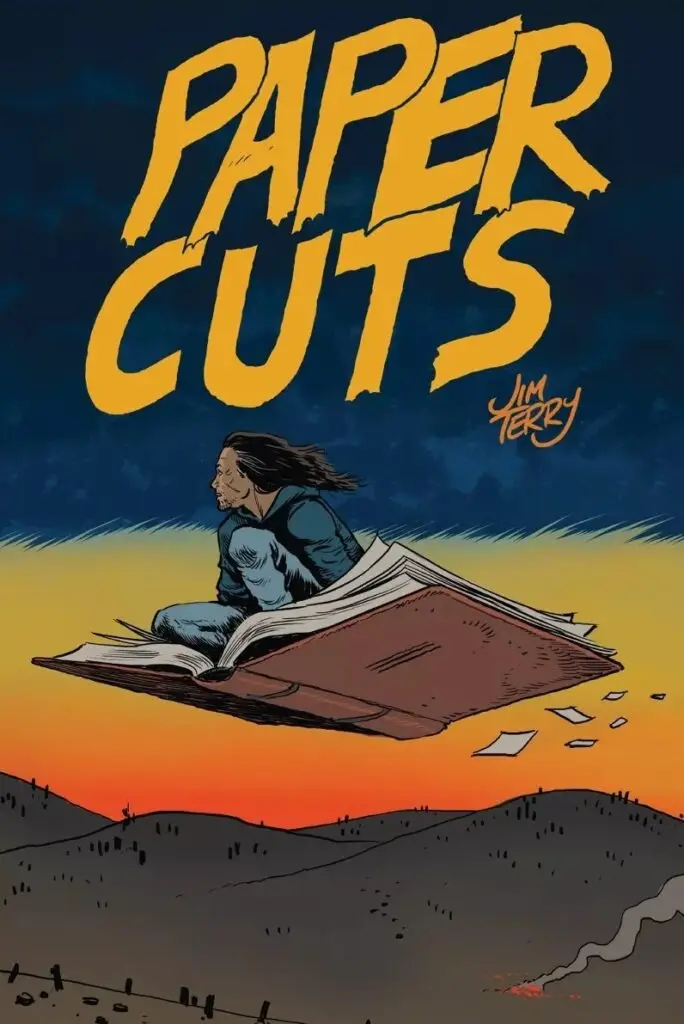

After attending the recent Native American Regalia and Dance Performance at the Newberry library, I walked through their current exhibition Indigenous Chicago, which was developed in partnership with Native community members and representatives from several tribal nations. It explores Indigenous history across five centuries to highlight the way that the development of the city has been shaped by Indigenous lives and land. I learned how the forced removal of Native peoples from their lands in what is now the city of Chicago was motivated by a desire to control and transform the environment in support of white settlement. The changes settlers made to these ecosystems transformed Chicago from an environment carefully managed by Indigenous people to support mutually beneficial habitats for plants, water, and animals into one that ultimately harmed these ecosystems in service of a settler economy. Before my somber exit, I find the largest comic book I have ever seen titled Paper Cuts by artist Jim Terry (Ho-Chunk), which was commissioned specifically for the exhibition. The book is opened to the last comic page that depicts a black and white scene of a long haired character with his back leaning on a tree with the following text: “Go find a tree to enjoy, hear the birdsong, pour some tobacco, get coffee with a friend, send your family a text, tell someone you love them, go feel the sun, the breeze, hear children laugh, walk in the rain. Don’t forget what was sacrificed and keep fighting in the ways you can. You are still occupied. You are still here. You are born of real survivors.” The words breathe a sense of hope into me as I walk out.

Left: The cover of Jim Terry’s graphic novel, Paper Cuts. Right: Christal Ratt (Algonquin of Barriere Lake), Shemaginish, birch bark set of Mandalorian armor.

While references to history are present in each of these six Native-centered exhibitions, the questions they pose and the art they present provide opportunities to center Natives moving forward. Set to open in January 2025, Living Stories: Contemporary Woodland Native American Art at the Mitchell Museum of the American Indian will feature Anishnabe artist Christal Ratt, among others yet to be announced. Ratt’s piece, Shemaginish references Indigenous futurism with a Mandalorian armor regalia made of harvested wiigwas (birch bark). I am reminded of the Center for Native Futures’ inaugural exhibition, Native Futures and how we imagine our futures to look. And maybe because I just attended the Regalia and Dance Performance at the Newberry Library and I have a great admiration for fashion, I also ask myself how will we dress? Regalia is incredibly special in Indigenous communities, and the evolution of the incorporation of contemporary iconography marks this current moment in time. A member of the Blackhawk Performance Company explained that Pow Wow Dances and the Regalia worn today are not static and change based on each dancer’s unique identity. Artists like Ratt are also future planning, keeping tradition in mind.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Luz Magdaleno Flores

Luz Magdaleno Flores @lightofyourvida is a Chicana with Purephecha lineage. She is an artist, photographer, writer, vinyl DJ, and bilingual editor for SixtyInchesFromCenter.org. Currently based in Chicago by way of Oxnard, California she aims to evoke feelings of nostalgia and melancholy for cultural and romantic memories in her artwork. You can read her words in the Chicago Reader and the South Side Weekly. Her photography and upholstery fabric project, Siento Un Dolor Pero Con Calma, is currently being exhibited at Harold Washington Library.