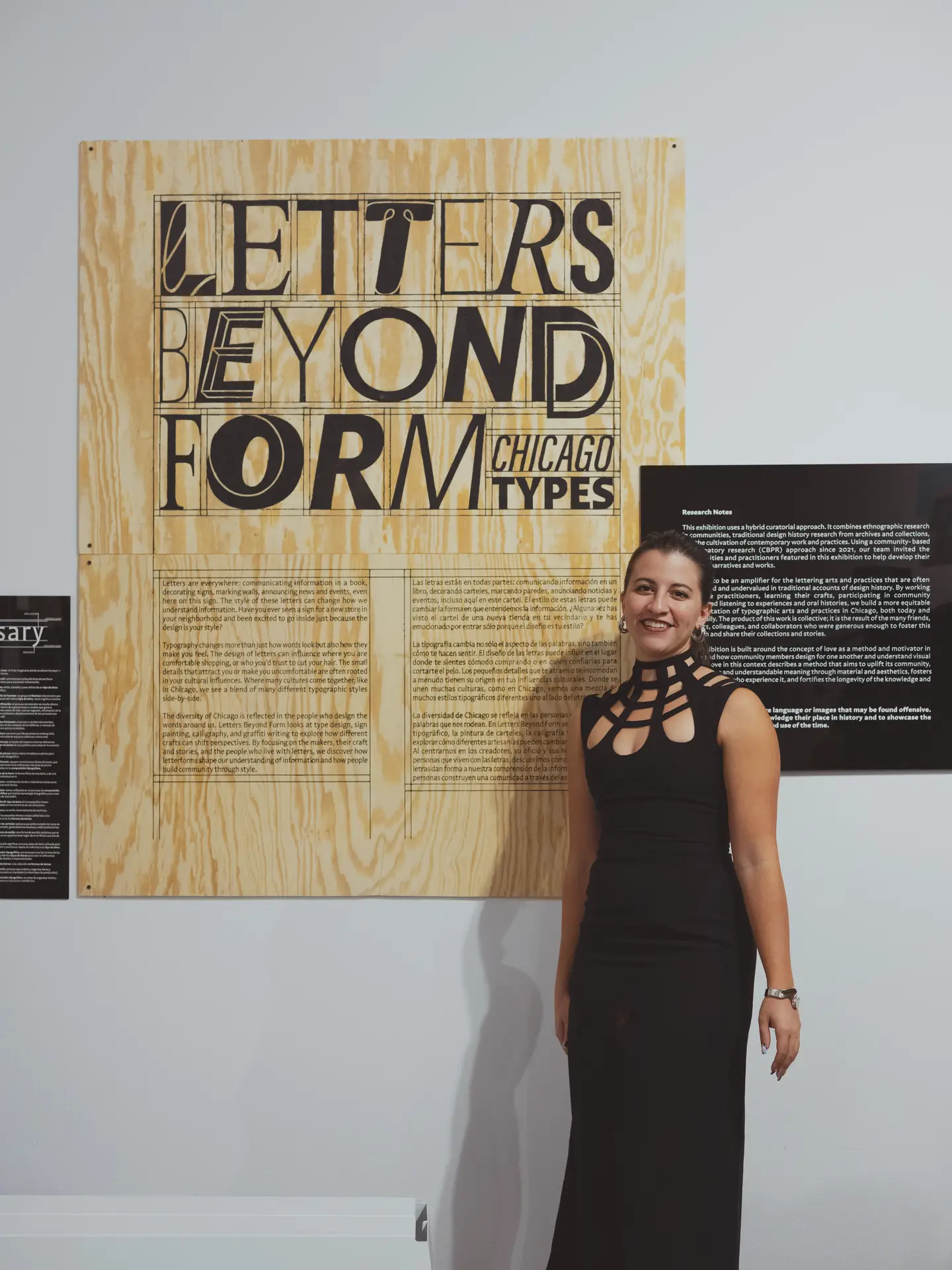

In the midst of the political and social upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s, Chicago became a stage for activism and protest, where art wasn’t just a tool for expression but a force for change. The city’s legacy of protest art during this period is a testament to how deeply intertwined art and activism are—especially when it comes to movements advocating for liberation and social justice. The Chicago History Museum’s exhibition, Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s–70s, offers a powerful exploration of this intersection.

In a conversation with the museum’s Director of Education, Erica Griffin, I learned that the exhibition doesn’t just revisit these historical moments; it seeks to reframe them, inviting visitors to reflect on how these past movements inform current struggles for justice and equality. Serving as a visual parallel for the current movements for justice and protest that erupted in 2023 for Palestine, the exhibit is a living reminder of the ongoing need for protest, activism, and resistance— how art remains a vital tool in the fight for liberation.

Art as Resistance

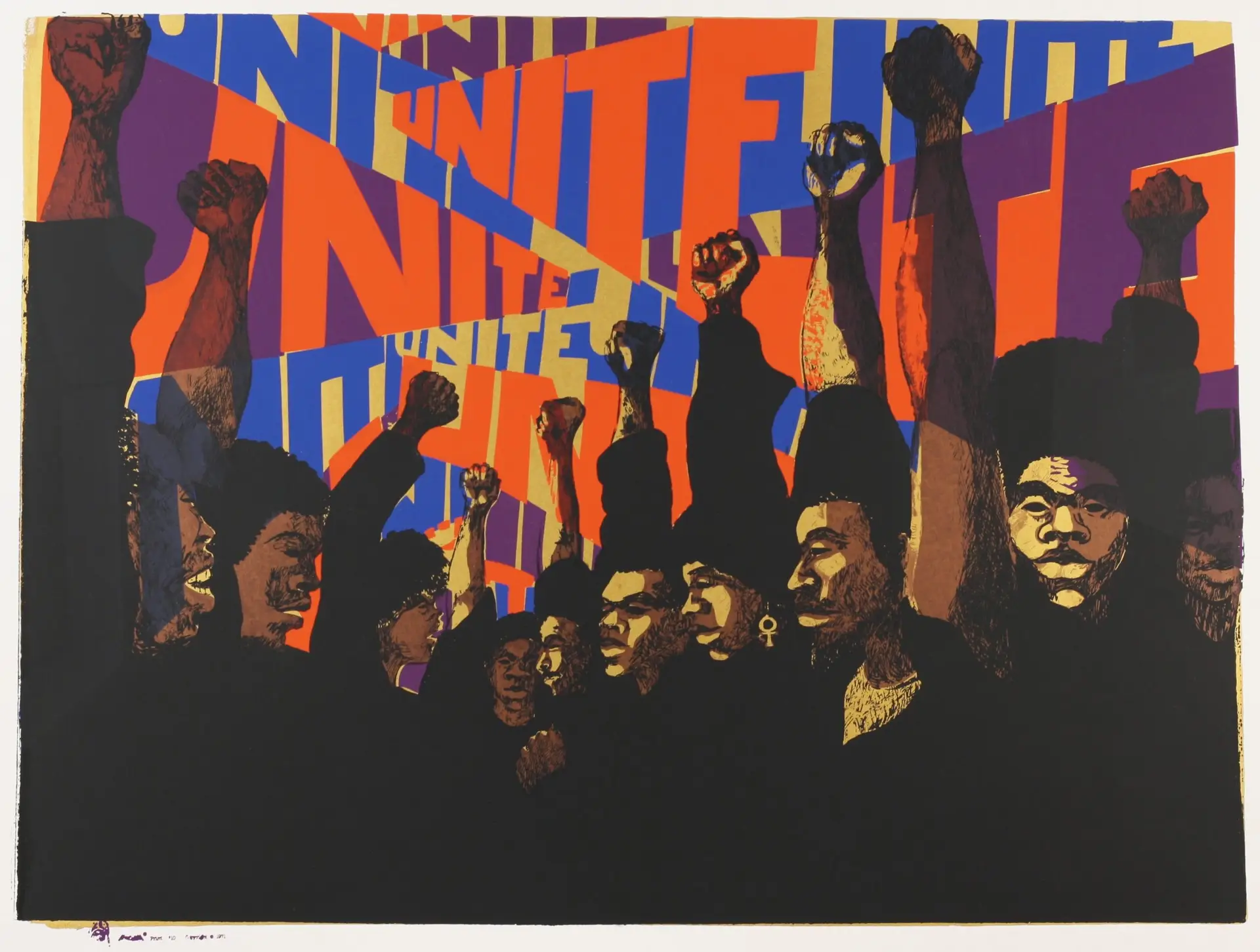

At its core, Designing for Change is a tribute to the role of art in resistance movements. Whether through posters, wearable art, or public murals, artists in the 1960s and 1970s used visual language to challenge systemic injustices. For Chicagoans, this meant addressing everything from racial segregation and police brutality to gender inequality and anti-war sentiment. “Art is an incredibly powerful medium, particularly in protest movements,” Griffin reflects. “It cuts across barriers. You don’t have to know the details of a political issue to feel the power of a visual image.”

In Chicago, that power was on full display in the 60s and 70s. From the Chicago Women’s Graphics Collective creating posters for feminist protests to Black artists crafting bold statements for the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, art became the mode of communication for activists across the city. The exhibition includes engravings, wearable art, and screen prints that capture the vibrancy and urgency of these movements, demonstrating how artists articulated both the collective anger and the vision for a more just society.

One of the most striking sections of the exhibition focuses on the 1960s and 1970s as a period of immense social change. Griffin explains, “This was a time when art and activism were symbiotic. They fed into each other. Artists were responding to the social movements around them, and in turn, their work galvanized more people to join these movements.”

This mutualistic relationship between art and activism is one of the exhibition’s central themes. It draws a direct line between the artistic output of the time and the broader societal shifts that followed, underscoring how cultural production was—and continues to be—a critical component of the fight for liberation from oppressive and unjust structures and forces.

Liberation Movements and Intersectionality

While the exhibition celebrates the role of protest art in Chicago’s history, it also confronts the complex dynamics within the movements themselves—especially when it comes to race, class, and gender. The women’s liberation movement, for instance, is portrayed in all its complexity. Though the movement fought for greater representation and rights for women, it wasn’t always inclusive. “There were significant tensions within the women’s movement, particularly around race,” Griffin explains. “Most of the leadership was white, and the concerns of Black women and women of color were often sidelined.”

The exhibit highlights these divisions by juxtaposing works from the Chicago Women’s Graphics Collective with those from the National Alliance of Black Feminists, a group that emerged in response to the exclusion of Black women’s voices within the broader feminist movement. The Black feminist group’s posters and banners focus on how the twin oppressions of racism and sexism shaped their experiences and political demands.

In one banner featured in the exhibition, the message is clear: Black women’s struggles for equality cannot be separated from the broader fight against systemic racism. This tension between race and gender within the liberation movement speaks to a recurring theme of intersectionality—a framework that acknowledges how various forms of oppression are interconnected.

For the museum, this honesty is essential. Griffin notes, “We wanted to tell the story of the women’s liberation movement in a way that reflects its complexity. Yes, it was about fighting for equality, but whose equality? And who was left out of that fight? We have to be transparent about those divisions if we’re going to understand the full scope of these movements.”

Equal Rights Amendment rally in Civic Center Plaza. ST-15001391-0003, Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum.

The Ethics of Storytelling

Another significant aspect of the exhibition is its emphasis on ethical storytelling. The museum took great care to ensure that the voices of marginalized communities were not only included but centered in the narrative. This approach stems from a broader institutional shift within the museum, which is working to become more inclusive and community-focused.

“Art institutions have often been guilty of telling stories from a singular perspective, usually that of the people in power,” Griffin highlights. “But that’s not the kind of museum we want to be. We want to make space for the communities we’re representing to tell their own stories.”

This ethos is reflected in the museum’s collaborative curatorial process. The exhibition was designed with input from a diverse advisory board that included community members, local artists, and scholars. Together, they shaped the exhibition’s narrative, ensuring that it reflected the lived experiences of those most impacted by the issues on display.

“We didn’t want this to be a top-down approach,” the Director explains. “This exhibition is about social justice, and that means we have to be accountable in how we tell these stories. It’s not enough to just put these works on display. We have to engage with the people whose stories we’re telling and make sure they’re represented accurately.”

One of the ways the museum is ensuring this accountability is by offering gallery guides and educational materials that encourage visitors to think critically about the art and the movements it represents. These guides ask visitors to reflect on the themes of the exhibition—protest, liberation, and justice—and consider how these issues manifest in their own lives.

“The goal is not just to inform people but to challenge them,” Griffin says. “We want visitors to leave here thinking about how they can be part of the ongoing fight for justice.”

Designing for Change isn’t just a celebration of the past—it’s a call to action for the present and future. The exhibition’s central message is clear: the fight for liberation is ongoing, and everyone has a role to play in it. Whether through art, activism, or education, the exhibit invites visitors to consider how they can contribute to the movements for justice that continue to shape our world.

For the museum, this means not only telling the stories of the past but also creating space for future movements to flourish. “We see this exhibition as the beginning of a larger conversation about how museums can support activism and social justice,” Griffin says. “We’re asking ourselves: How can we be a resource for the communities we serve? How can we use our platform to amplify voices that have historically been silenced?” These are the questions that guide the museum’s future work, as it seeks to become a space that not only preserves history but actively participates in shaping a more just society.

For visitors, Designing for Change offers a chance to engage with the legacies of protest and liberation that have defined Chicago—and to reflect on how those legacies continue to influence the city’s present and future. It’s an invitation to learn from the past, but also to act in the present, in pursuit of a more equitable and just world.

In this context, the ongoing protests for Palestine in Chicago are a natural continuation of the city’s legacy of resistance, blending the past with the present in profound ways. Over the years, Chicago has become a hub for Palestinian solidarity, with protests calling for an end to the Israeli occupation, and justice for the Palestinian people. The protests that erupted in October of 2023, part of the broader justice for Palestine movement, have reignited the city’s activist spirit, drawing thousands into the streets. These protests, like their predecessors in the 1960s and 1970s, reflect the power of collective action and visual resistance—banners, posters, and murals all speak to a unified demand for freedom and equality. Chicagoans of various backgrounds have rallied together, with Palestinian, Black, and Indigenous voices prominently calling for liberation and an end to the U.S.-backed Israeli genocide of Palestinians, connecting the struggle for Palestinian liberation to other global movements against oppression and colonization. Unfortunately, the protests have also been met with an unnecessarily hardlined police response, with many demonstrators reporting the use of excessive force and mass arrests, echoing a familiar pattern of state suppression of dissent seen throughout Chicago’s history.

Left: Protestors gather at the Congress Plaza around The Bowman (c. Ivan Meštrović, 1928) in preparation to march against the Israeli occupation of Palestine, Oct. 14, 2023. Right: An activist holds a hand-made sign that combines the Palestinian flag and a dove holding an olive branch, Oct. 21, 2023. Photos by Fariha Koshul.

The legacy of police brutality has long been intertwined with the fabric of social movements in Chicago, stretching back to the civil rights and Black power movements of the 1960s and 1970s. During that time, figures like Fred Hampton and the Black Panther Party became central to the city’s resistance against police violence and systemic racism. The infamous assassination of Hampton by the Chicago Police Department in 1969 exemplified how state violence was wielded to suppress movements for Black liberation. Today, echoes of those struggles resurface in the fight against modern police violence, from the murder of Laquan McDonald in 2014 to the protests against police brutality in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, to the calls for demilitarization and anti-state surveillance embedded in the pro=Palestine protests.

Designing for Change inadvertently becomes a living dialogue with the Palestine solidarity movement. The parallels between past protest art and the current visuals emerging from Chicago’s streets are striking—whether it’s the iconic keffiyeh-clad figures in solidarity marches or the murals honoring Palestinian martyrs, art continues to serve as a language of resistance. In addition, the intersectionality of Chicago’s protests today echoes the solidarity movements of the past, where racial justice, anti-imperialism, and anti-colonialism were and remain deeply interconnected. In many ways, the exhibition underscores that while times may change, the need for protest art, resistance, and the demand for justice are ever-present, uniting local struggles with global liberation movements.

This ongoing activism around Palestine aligns with the exhibition’s broader message: protest is not confined to any one era or cause. Rather, it’s a practice that evolves, building upon historical legacies to address new injustices. As Chicago continues to witness protests advocating for the end of the occupation and freedom for Palestinians, the exhibition provides a critical framework for understanding how art, activism, and resistance are intertwined across generations, making the call for justice timeless and universal.

As the Director of Education puts it: “Protest is not a moment. It’s a practice. And it’s one we need now more than ever.”

Protest as an Ongoing Practice

While the exhibition looks back at the 1960s and 1970s, it does so with an eye toward the present. In many ways, the struggles of that era are not so different from the struggles of today. The themes of protest, liberation, and social justice remain as relevant as ever, especially in a city like Chicago, where issues of inequality and injustice continue to shape daily life.

“The exhibit is as much about the present as it is about the past,” Griffin says. “We wanted visitors to see that the fights for racial justice, gender equality, and economic fairness didn’t end in the 1970s. Those struggles are still happening today.”

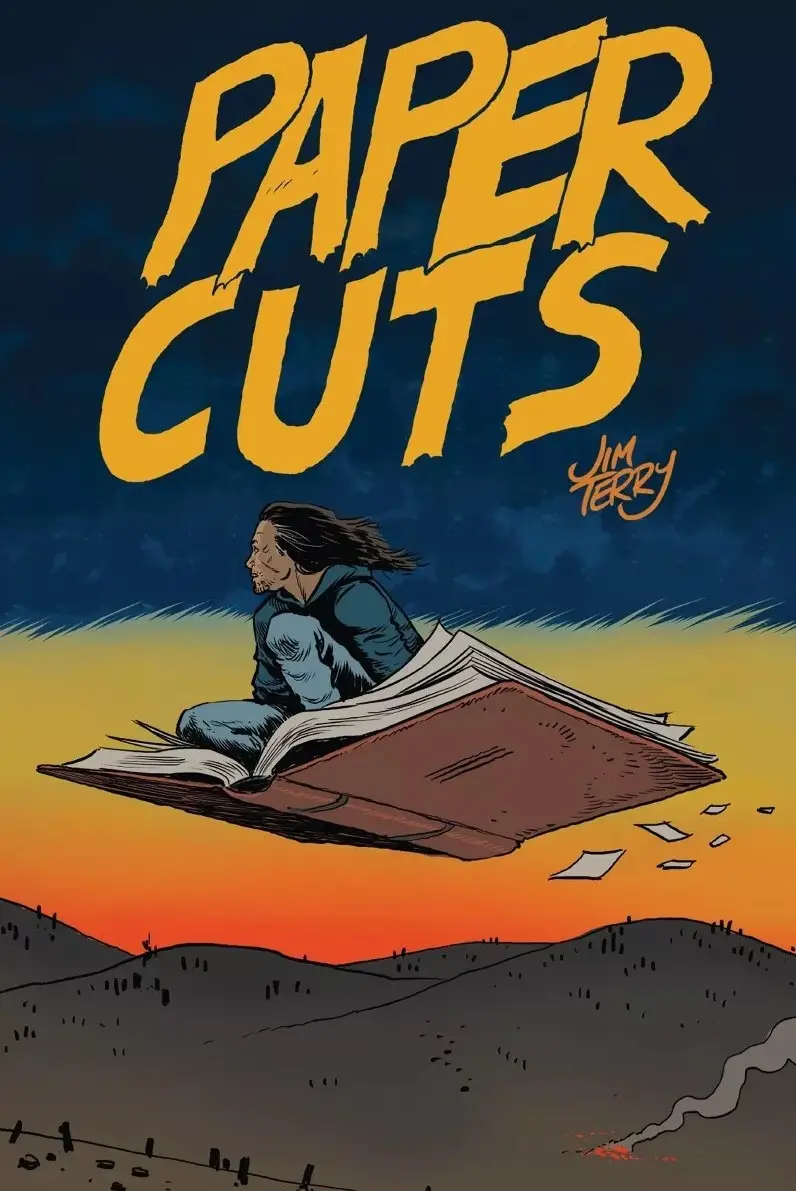

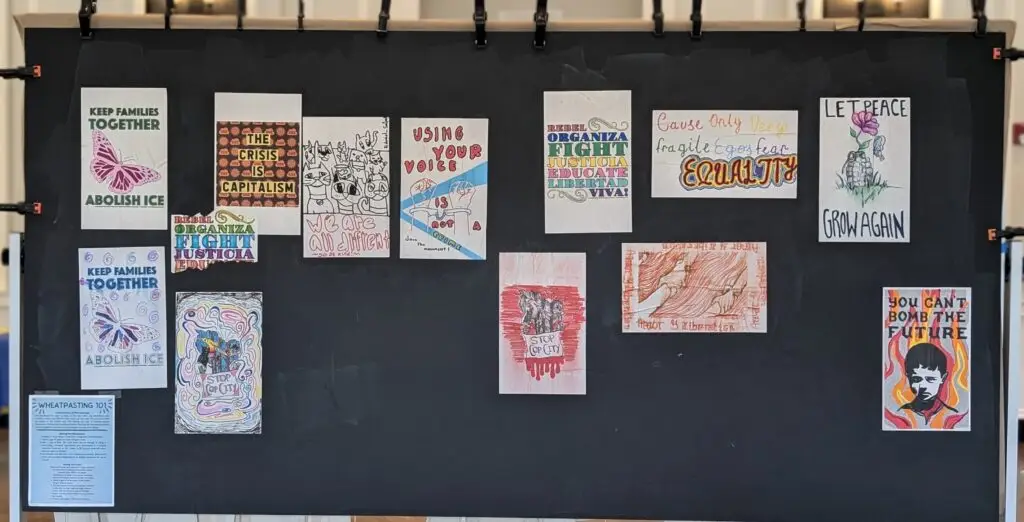

This connection between past and present is especially clear in the exhibition’s focus on contemporary youth engagement. A cohort of Chicago teens was involved in the curation process, creating their own works of protest art in response to the historical pieces on display. Through a four-week long Artivist internship, held from early July to August, the teens learned about the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s and, more importantly, drew powerful parallels to the issues they face today.

“Teens today are grappling with many of the same concerns,” the Director of Education notes. “Race, gender, economic inequality—these issues haven’t gone away. What we’re doing through this program is giving them the tools to respond to those issues through art, just as the artists in the 60s and 70s did.” Giving teens this space and opportunity is key to ensuring their voices are heard in spaces where they are often overlooked. They represent the next generation of leaders, and in order for them to navigate and make sense of these spaces, they must understand the historical moments that have shaped the society they live in today. This program primes them for civic involvement and helps them reflect on how they can inform our society tomorrow.

A core goal of the program was to bring a more diverse group of young people into the arts and museum fields, where diversity is still lacking. “When I was growing up, there weren’t programs like this,” Griffin reflects. The Artivist program aims to make museum work more accessible and aspirational for teens from all backgrounds, offering them a chance to see museums as spaces where their stories and histories are not only preserved but also actively shaped by them. “It’s meaningful to me that these teens can think of museum work, arts, and culture—especially history museums—as viable career options.”

The program’s roots lie in a previous teen engagement initiative the Director led at the museum during the pandemic, where teens created a digital scrapbook reimagining historical Black spaces in Chicago, like the Negro Fellowship League (founded by Ida B. Wells and her husband Ferdinand Barnett in 1910) and the Elam House (founded by Melissia Ann Elam in 1926), as if they were still active today. This earlier project inspired the idea of building deeper teen engagement and arts-centered experiences around future exhibitions, especially those focused on social movements.

For the Artivist program, teens applied from across the city, and the museum received an overwhelming response with over 80 applicants. Ultimately, the program could only accommodate eight participants, but the Director emphasized that they hope to keep engaging the broader group in future projects. The selected cohort, diverse in both background and interests, was united by their passion for social justice and a desire to use art as a vehicle for activism. They didn’t need any prior artistic skills—just a willingness to learn, engage, and participate.

Posters designed by the Artivist cohort presented at their multimedia collection showcase, Aug. 3, 2024. Photo by Fariha Koshul.

One of the most profound outcomes of this program has been the formation of this teen cohort, which collectively decided to create a unified response to today’s injustices. Inspired by historical art collectives like AfriCOBRA, the teens decided to address these issues together. The teens’ art—created through screen prints, murals, and poetry—is now woven into the exhibition, serving as a powerful testament to the enduring relevance of protest art. They tackled issues like race, gender, economic inequality, and militarization, mirroring the themes of the 1960s and 70s but with their own unique perspectives shaped by the realities of today. The teens were fully immersed in the historical context of the exhibition, meeting with the museum’s staff—everyone from curators to security personnel—to understand the full scope of how exhibitions come together. They learned not only about the artistic movements of the past but also about the behind-the-scenes work of museum operations, including how to prepare objects for display and ensure the museum is accessible and secure for visitors.

Throughout the program, the teens engaged deeply with the social movements featured in the exhibition, gaining hands-on experience with the arts techniques of the 60s and 70s. They were encouraged to think critically about how those movements resonate today, and their responses have been nothing short of inspiring. ‘They’ve come up with the most beautiful, honest, and detailed expressions of what they want to say and how they want to say it,’ Griffin said. The result is a series of artworks that not only reflect the teens’ collective vision but also emphasize the power of youth voices in shaping the future of activism and art.

The Director also expressed excitement for the future of the program, noting that these kinds of teen-led initiatives can help redefine how museums engage with communities and tell Chicago’s stories. The hope is that this is just the beginning. These teens have power, and their voices, when they come together, are transformative. The program has given these young people the tools to express themselves, and in return, the Director admits to learning as much from them as they did from the program. “I’m a lifelong learner. These young people have taught me so much—about resilience, about collaboration, and about the power of their generation to make change.”

Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s–70s is on view through May 18, 2025 at the Chicago History Museum.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Fariha M. Koshul

Fariha Koshul, a Chicago-based writer for Terra Foundation for American Art, combines her academic training in ethics, anthropology and sociology with practical experience in digital curation, collections management and archiving. Her time at the University of Chicago involved leading research projects and collections care aimed at incorporating ethical practices in diverse cultural contexts. Fariha’s work is marked by a deep commitment to an understanding of the ethical implications of working with anthropological material, specifically in curatorial and museum spaces, and to the promotion and preservation of cultural, artistic and faith-based narratives and communal and social histories.